This website uses cookies. Find out more in our Privacy Policy.

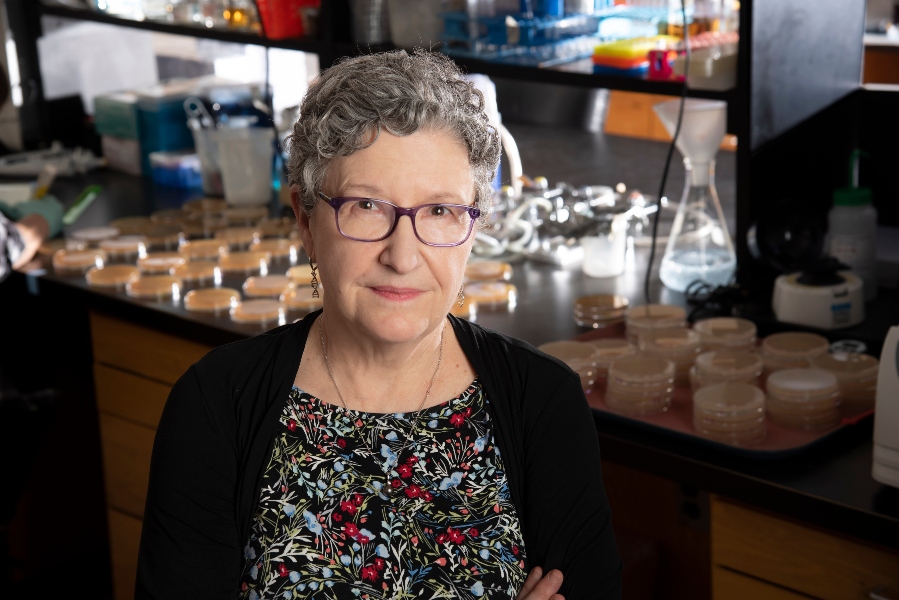

Sue Jinks Robertson '77

Sue Jinks- Robertson '77 shines in the science field and receives its top honor

During her time at Agnes Scott College, Sue Jinks-Robertson ’77 spent most afternoons in the lab that went along with her science classes. As a result, she missed out on being involved in many extracurricular activities. But the lab was exactly where she wanted to be.

“I was always good at science,” she says. “I enjoyed the problem-solving aspect of it, and I loved being in the lab.”

This talent for science and love of being in a lab has been a constant in Jinks-Robertson’s career. She has spent more than 30 years in the academic world, teaching, publishing and conducting research in the area of human genetics. Today, she is a professor and co-vice chair in the Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology in the Duke University School of Medicine, as well as director of Duke’s cell and molecular biology graduate training program. She is also a fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and was recently named Mary Bernheim Distinguished Professor by Duke University School of Medicine. And in April 2019, she received what those in the science field consider the highest honor: election into the National Academy of Sciences.

As a biology major at Agnes Scott, Jinks-Robertson’s interest in genetics was sparked when she took her first genetics class taught by Harry Wistrand, who is now professor emeritus of biology.

“That was it,” she says. “I fell in love with genetics, and I knew that was the field for me.”

Jinks-Robertson came to Agnes Scott from her hometown of Panama City, Florida. When she was considering colleges, her mother compiled a list of only women’s colleges. Among the factors that led her to choose Agnes Scott were the beauty of its campus and the fact that four other girls from her high school were also attending the college. Being educated at a women’s college helped build the foundation for success in her career.

“For me, coming to a women’s college was a good thing,” she says. “I gained a lot of confidence, and I felt I could hold my own in a male-dominated field. I don’t know if that would’ve been the case had I gone to a coed college.”

Jinks-Robertson may have not had a lot of time for activities outside her classes — though she was a member of the Dolphins synchronized swimming club — but she did establish lifelong friendships during her four years at Agnes Scott. She is part of a group of about 10 former Scotties that still gets together several times a year. She also maintains a fondness for some of her professors who played a role in her education.

Sue Jinks-Robertson ’77 celebrated her election to the National Academy of Sciences for her outstanding contributions to research with Duke University students in her lab. Front row: Wei Zhu (left) and Eva Mei Shouse. Back row, from left to right: Dionna Gamble, Nicole Stantial, Samantha Shaltz, Robertson, Asiya Gusa and Demi Zhu. Photo courtesy of Sue Jinks-Robertson ’77.

Since leaving Agnes Scott, Jinks-Robertson has long stayed in touch with Wistrand, who mentored her as a budding geneticist. The other professor who had an impact on her was the late Professor Emerita of English Margaret Pepperdene, who taught two Chaucer classes when Jinks-Robertson was a student.

“It was taught in Old English,” she remembers, “so I spent hours in the library going through the Old English dictionary to translate what I was reading.” She says those classes and the other English classes she was required to take helped her become a strong writer.

“They taught me to be precise, which is very valuable,” she says. “And that’s something I continue to encourage my students to do today.”

After graduating from Agnes Scott, Jinks-Robertson earned a doctorate in genetics from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in 1983. She also married her late husband, John, and they had three children. She went on to complete postdoctoral research at the University of Chicago, and then accepted a position at Emory University in 1987. She worked in the Department of Biology there for almost 20 years, teaching Introduction to Genetics as well as several upper-level graduate classes.“I enjoyed teaching, but it didn’t leave a lot of time for research,” she says.

So when her postdoctoral mentor, Thomas Petes, who was then-chair of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke, called to encourage her to apply for an open faculty position, she jumped at the chance to focus more on research. She and her family moved to North Carolina in 2006.

Now Jinks-Robertson oversees a lab where the majority of the research is studying genome stability. She uses budding yeast (the yeast used in making beer) as a model genetic system.

“The mechanisms uncovered both in bacteria and yeast are similar to what goes on in human cells,” she says. “What we learn in yeast is directly applicable.”

She is studying the processes that lead to destabilization of genetic material, which can cause problems in the human body. This research has direct implications in cancer research, as the disease is characterized by rampant genome instability.

“You see the same thing in cancer/tumor cells,” she explains. “There are distinctive mutation signatures that show up in cancer cells, but what is causing them is not often known. That’s where the link comes in.” She runs a lab of all women, which she admits is unusual, and is happy it is also a small lab.“I’d rather run a lab where I can effectively mentor people,” she says, adding that she believes she encourages women in science by being a role model.

Jinks-Robertson became even more of a role model last May, when she received the news she always dreamed of but never expected. Petes called from the annual meeting of the National Academy of Sciences to tell her that she was elected into the prestigious organization whose members are nominated for their outstanding contributions to research.

“I was stunned,” she says. “I had no idea, and that was the best part. Some people expect it, but I didn’t.”The first person Jinks-Robertson says she would have called was her husband, but sadly he passed away in 2016.“John was my biggest cheerleader,” she remembers. “He would have been thrilled.”

Instead, she called her oldest son, who is also a scientist, knowing he would understand the significance. As word got out, she was inundated with calls and emails.“It was so nice hearing from so many colleagues and friends,” she says. “Becoming a member of the National Academy of Sciences is a significant recognition and achievement of a career.”

And this long and remarkable career of a woman leading in science had its beginning at Agnes Scott.

Read more stories from the Spring edition of Agnes Scott the Magazine here.